Climate in Context

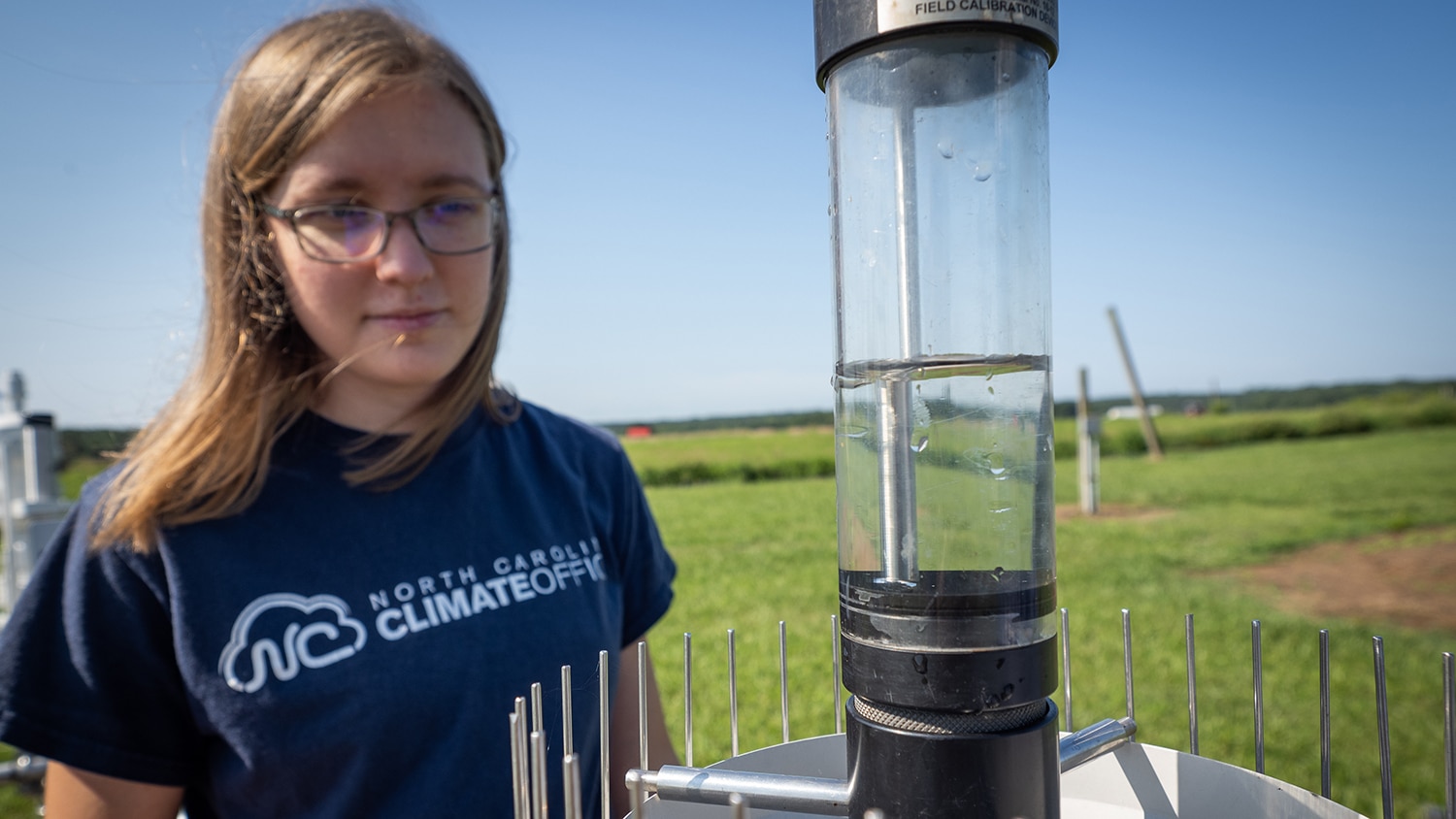

The State Climate Office of North Carolina, a unit of the College of Sciences, helps the state’s residents understand how weather and climate affect them.

In August, residents of rural Haywood County, N.C., located in the mountains west of Asheville, were stunned by catastrophic flooding caused by the remnants of Tropical Storm Fred. They knew the storm would bring rain — but nobody expected enough to make the rivers rise more than three feet in an hour, with one of them cresting at more than 19 feet.

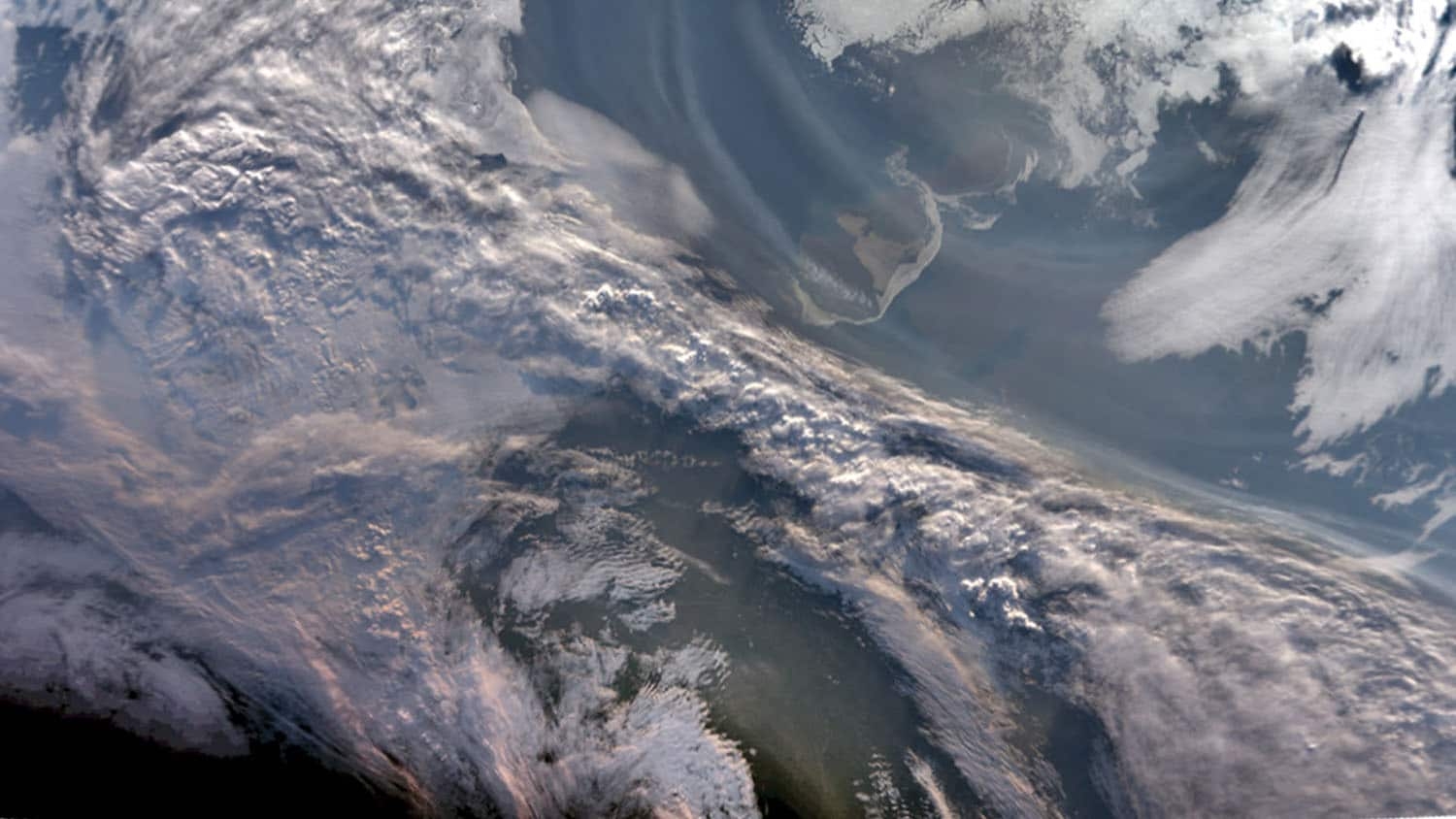

This was only the latest in a series of extreme weather events to affect the state in recent years. As the impacts of climate change continue to be felt around the world, these events have become more common.

“These disasters are coming at us so fast that even unprecedented events like the Haywood flooding, which killed six people, are quickly forgotten,” said Kathie Dello, the director of the State Climate Office (SCO) of North Carolina. “Events like this show us that we’re entirely unprepared to handle our changing climate.”

Dello’s team wants to help North Carolinians be more prepared for these types of events — and more informed about what they mean for both their everyday lives and the future.

Leadership Through Partnership

North Carolina’s State Climate Office has long been a leader nationally, but its efforts amplified in 2019 when Dello became its fifth permanent director and the first woman to lead the office. She was previously deputy director of the Oregon Climate Change Research Institute and worked extensively at the intersection of climate science and public policy, including positions on Oregon’s Water Supply Availability Committee and Drought Readiness Council.

She was drawn to the office because of its location on the East Coast and its reputation and immediately saw the opportunity to have an even bigger impact on the state.

“I applied to the job just after Hurricane Florence hit North Carolina, and that was such a clear example of climate change showing up in the present day,” Dello said.

Dello now leads a 10-person team, based on NC State’s Centennial Campus, that is part of the College of Sciences. Her office is one of the largest and most active state climate offices in the nation.

The aim of the SCO’s work is to make the science of weather and climate accessible to the public. The office does this by focusing primarily on three areas: research, extension and education, and monitoring. Through its work, the SCO reaches citizens in all 100 of North Carolina’s counties.

“We’re telling the story of a rapidly changing North Carolina.”

“We aim to put climate-related events into context,” Dello said. “We’re telling the story of a rapidly changing North Carolina.”

The team frequently partners with other climate offices in the region, as well as government agencies and researchers at other universities.

One of these partners is North Carolina Emergency Management (NCEM). The SCO supplies NCEM with statistics and graphics about weather events that help clarify the impact of those events and also provides information relevant to state and federal disaster declarations.

“The team at the North Carolina State Climate Office are wonderful and invaluable partners for us,” said Diana Thomas, a meteorologist with NCEM. “Every time we reach out with climatological questions the team goes above and beyond in providing detailed presentations.”

Data-Driven Outreach

Data are key for Dello’s team, and a big part of their work involves connecting the public with these data through reporting tools — and helping them understand what the information means.

In May 2021, the SCO launched Cardinal, a free, one-stop tool for historical North Carolina climate data. For example, Cardinal users can chart accumulated precipitation over the course of the current year and compare it to the wettest and driest years on record.

Since its launch, the system has received more than 36,000 visits. “We wouldn’t be able to handle all of those requests individually. It’s really been an invaluable tool for us and our partners,” Dello said.

The SCO also gets 1.5 million data observations per day via the North Carolina Environment and Climate Observing Network (ECONet), a series of 43 observation towers across the state that constantly measure atmospheric and soil parameters like atmospheric temperature and soil moisture. Visitors to the SCO site can access data from each station, and state and federal agencies also use this information.

Sometimes, the SCO team’s job involves talking to constituents on a more personal level to help them understand what these data mean for their everyday lives.

“People call us because they want to know if they can hold an outdoor wedding six months from now or plant their tomatoes without threat of frost,” Dello said. “These questions show just how personal climate really can be. It touches all of us in all parts of our lives.”

The SCO’s blog and social media channels also serve as means of breaking down the significance of weather and climate events and trends for the public. Recent blog posts have looked back on the impact of Hurricane Matthew five years later and looked ahead at the winter weather outlook for the state.

To further amplify their message, the SCO also works with N.C. Cooperative Extension agents across the state to help them understand climate risks and impacts. The agents then take this information out into the communities they work with, who see them as a trusted source of information.

The SCO also collaborates with The Science House, the college’s K-12 science outreach arm, to help students understand weather and climate. This includes releasing classroom activities and lesson plans for teachers to use.

New Ventures

Recently, the SCO has undertaken some larger research partnerships that will expand the effect of their outreach within — and beyond — the state.

In September, Dello was announced as a co-lead on a $5 million project from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) titled “Innovating a Community-Based Resilience Model on Climate and Health Equity in the Carolinas.” The project is one of 11 funded by NOAA’s Regional Integrated Sciences and Assessments Program, which is designed to increase collaboration around climate change adaptation research.

This five-year multi-institutional effort, which also involves researchers from the university’s North Carolina Institute for Climate Studies and the College of Natural Resources, will study climate resilience solutions in communities in the Carolinas that have been hit particularly hard by the climate crisis.

“Extreme weather and climate events impact every community, but not all communities are affected equally,” Dello said. “Frontline communities disproportionately feel the impacts of these events.”

The team will partner with two communities in western North Carolina and coastal South Carolina to understand how existing infrastructure issues, historical discrimination, disinvestment and health inequities can compound the effects of climate events like heat waves, hurricanes and flooding. They hope to help the communities develop resilience strategies and build community-level climate literacy by implementing community science programs.

In another recent community-based project funded by NOAA, the SCO worked with organizations all over the Triangle on a citizen science project to map heat islands in Raleigh and Durham. Volunteers collected real-time data that included ambient temperature and humidity that will be used to create a high-resolution temperature map of the two cities, showing which areas suffer the worst effects of summer heat.

Dello says the data gathered through this project will lead to real solutions to help local residents stay cooler.

Both of these projects are examples of the SCO’s dedication to working with, and within, local communities to help them in practical ways.

“We hear from people often who are deeply concerned about the climate crisis and thinking about their families and their livelihoods,” Dello said. “People want to know about how to be proactive, and we want to empower them with the information they need to take whatever steps they can.”