Researchers Create More Complete Picture of Freshwater Toxic Algal Blooms

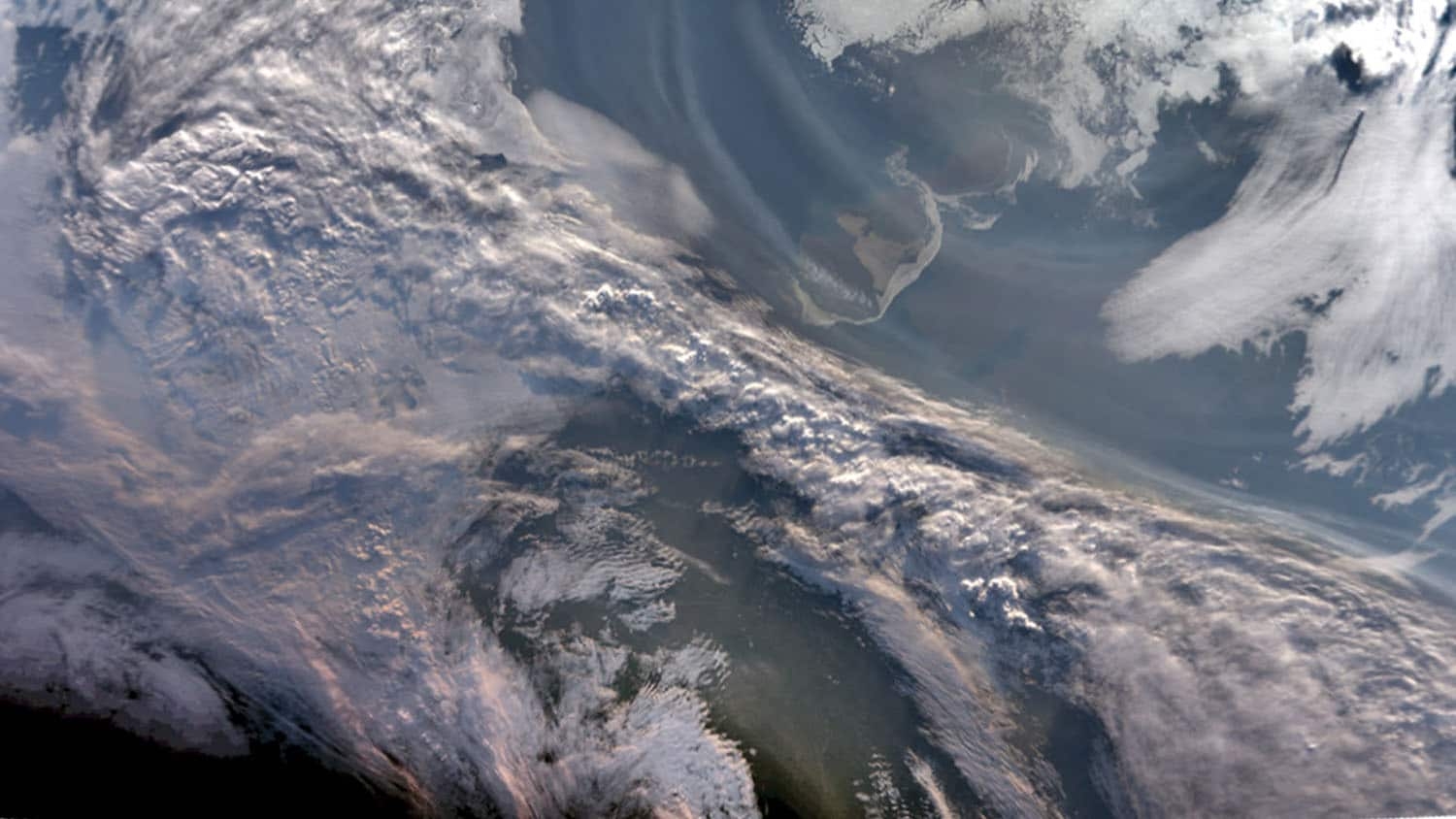

Using two different measurement methods, researchers from North Carolina State University conducted a two-year study of North Carolina’s Jordan Lake in which they monitored toxic algal blooms. The researchers found that multiple cyanotoxins from toxic algal blooms are present year-round, albeit in very low concentrations. Their findings could improve the ability to predict toxic blooms.

Freshwater algal blooms have increased due to nutrients from sources such as fertilizers and other agricultural runoff entering the water. While every algal bloom isn’t toxic – some algal species can produce both toxic and nontoxic blooms – toxic blooms can cause problems for swimmers and other recreational users in the form of rashes or allergic reactions.

“We’ve confirmed both that the toxins are there year-round and that multiple toxins are there simultaneously but in very low levels,” says Astrid Schnetzer, associate professor of marine, earth and atmospheric sciences at NC State and corresponding author of a paper describing the research. “First, let’s be clear that the presence of the toxins doesn’t affect drinking water – treatment plants scrub all of that out. Secondly, the amounts of toxins we did find are about an order of magnitude below safe levels, so that’s also good news.”

Schnetzer and former NC State graduate student Daniel Wiltsie wanted to know which cyanotoxins were present in Jordan Lake, a major drinking water reservoir in central North Carolina.

From 2014-16 Schnetzer and Wiltsie sampled the lake water in two ways: by taking discrete samples (in which water is collected in a container) and by using solid phase adsorption toxin tracking (SPATT) bags, which are left in the water for a period of days or weeks. SPATT bags contain an absorbent resin that captures dissolved toxins. “By using two methods we were better able to determine what the concentrations looked like over time,” Schnetzer says. “Algal blooms are ephemeral, so it’s possible to completely miss them if you only look at discrete sampling. SPATT bags give you data on how the toxins can accumulate and overlap.”

The researchers analyzed the samples for five different toxins, and found four of them: microsystin, anatoxin-a, clindrospermopsin, and β-N-methylamino-L-alanine (BMAA). Multiple toxins were detected at 86 percent of the sampling sites and during 44 percent of the sampling events.

“This study is the first to use both SPATT bags and sampling to assess the toxins in the water,” Schnetzer says. “It’s a first step toward creating better informed approaches to really understanding the frequency and magnitude of these blooms.

“In the future, we want to have a better predictive capability regarding these blooms as well as the ability to identify new emerging toxins. The data may also help us determine risk from chronic low-level exposures, as well as tease out what risks derive from exposure to multiple toxins at once.”

The research appears in Toxins and was supported through funds from the Urban Water Consortium/Water Resources Research Institute (grant 16-11-U) and North Carolina Sea Grant (5104348). Schnetzer is corresponding author and Wiltsie is first author. The study was made possible through a partnership with Jason Green, Mark Vander Borgh and Elizabeth Fensin from the N.C. Department of Environmental Quality’s Division of Water Resources.

-peake-

Note to editors: An abstract of the paper follows

“Algal Blooms and Cyanotoxins in Jordan Lake, North Carolina”

Authors: Daniel Wiltsie, Astrid Schnetzer, North Carolina State University; Jason Green, Mark Vander Borgh, Elizabeth Fensin, North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, Division of Water Resources

Published: Toxins

Abstract: Eutrophication of waterways has led to a rise in cyanobacterial harmful algal blooms (CyanoHABs) worldwide. The deterioration of water quality due to excess algal biomass in lakes has been well documented (e.g., water clarity, hypoxic conditions) but health risks associated with cyanotoxins remain largely unexplored in the absence of toxin information. This study is the first to document the presence of dissolved microcystin, anatoxin-a, cylindrospermopsin, and β-N-methylamino-L-alanine in Jordan Lake, a major drinking water reservoir in North Carolina. Saxitoxin presence was not confirmed. Multiple toxins were detected at 86% of the tested sites and during 44% of the sampling events between 2014 and 2016. Although concentrations were low, continued exposure of organisms to multiple toxins raise some concerns. A combination of discrete sampling and in-situ tracking (Solid Phase Adsorption Toxin Tracking [SPATT]) revealed that microcystin and anatoxin were the most pervasive year-round. Between 2011 and 2016, summer and fall blooms were dominated by the same cyanobacterial genera, all of which are suggested producers of a single or multiple cyanotoxins. The study’s findings provide further evidence of the ubiquitous nature of cyanotoxins and discusses the challenges involved in linking CyanoHAB dynamics to specific environmental forcing factors.

This post was originally published in NC State News.