Study: Columbus’ Caribbean ‘Cannibal’ Claims Were Correct

For centuries, scholars have discounted Christopher Columbus’ reports of a population of cannibals that raided other peoples in what are now The Bahamas and Hispaniola. New evidence suggests Columbus was right, and that he encountered the warlike Carib people, which he called “Caniba” (though it’s still not clear if they actually ate people).

The finding upends the conventional picture of what Caribbean peoples looked like before the arrival of Europeans – and where those populations came from. A paper on the work, “Faces Divulge the Origins of Caribbean Prehistoric Inhabitants,” was published Jan. 10 in the journal Scientific Reports.

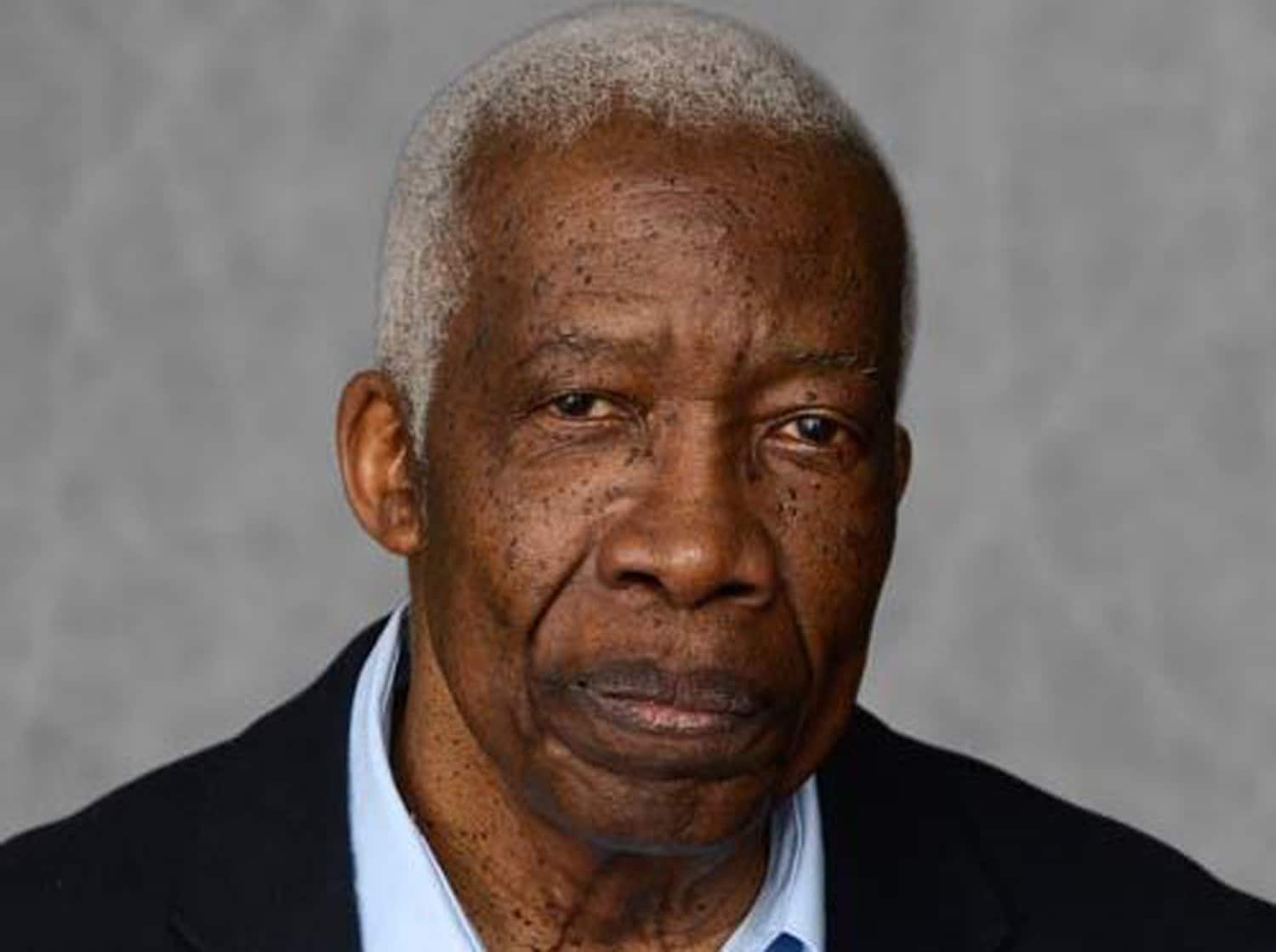

The leaders of the study were Ann Ross, a biological anthropologist and professor of biological sciences at NC State University, and William Keegan, curator of Caribbean archaeology at the Florida Museum of Natural History.

We recently sat down with Ross to learn more about the work.

The Abstract: What’s the fundamental new idea here?

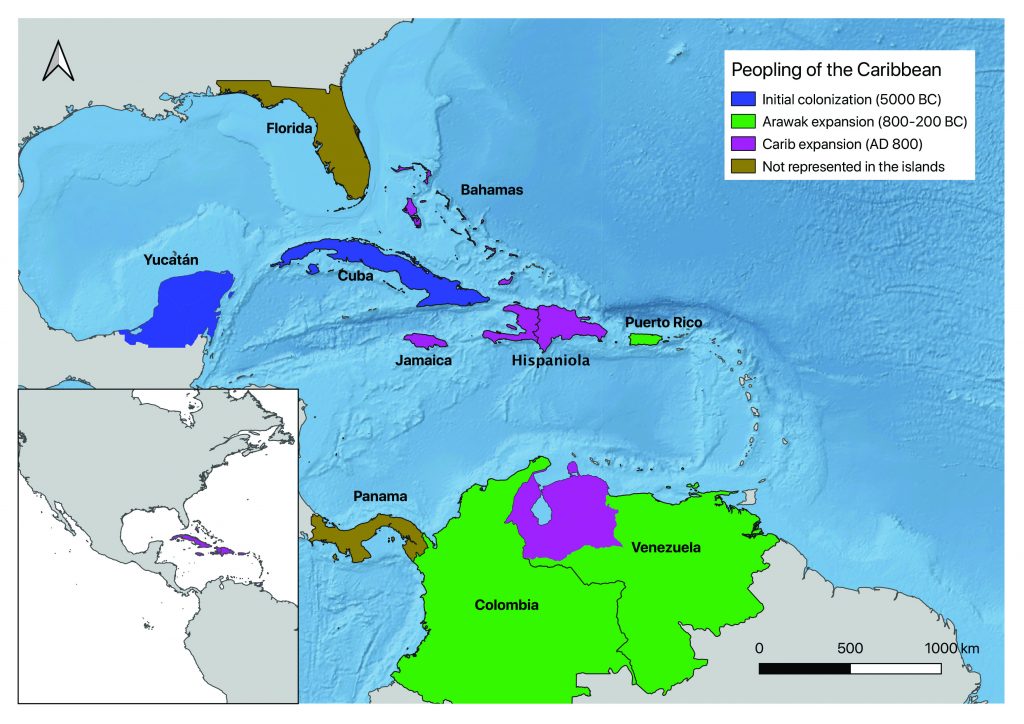

Ann Ross: The big idea is that anthropologists thought there were two waves of pre-Columbian migration into the Caribbean. One that came up from South America into the Lesser Antilles, like Grenada and Guadeloupe, and another that came from the Yucatán up through Cuba. What we’ve found indicates that there was a third wave, separate from the others.

TA: What does this have to do with the Carib people?

Ross: The Carib people were the third wave. Until now, it was thought that the Carib didn’t make it past Guadeloupe. But our work indicates they made it as far as The Bahamas. [See map at bottom of page.]

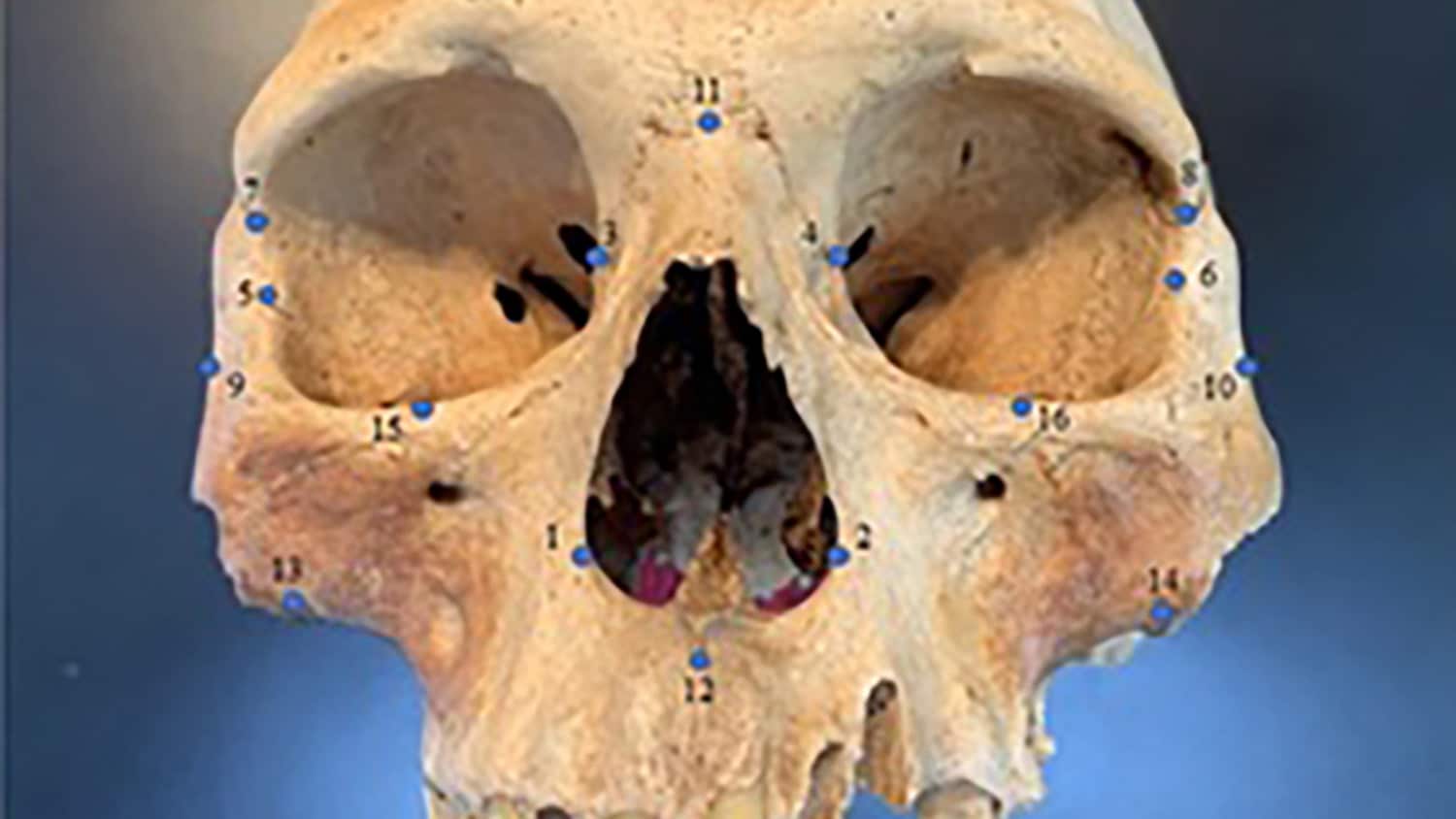

One of the things that we brought to the table with this study was an analysis of the facial morphology of pre-Columbian remains found in The Bahamas and other islands in the region.

TA: What can you learn from analyzing these skulls?

Ross: We know that the Carib practiced artificial cranial modification, meaning that they engaged in a practice called “skull flattening” to produce particular characteristics. That’s fairly easy to spot. But to really track a population you need to focus on heritable characteristics – things that are passed on genetically. In order to do that, we focused on analyzing facial characteristics.

This involved taking detailed, three-dimensional measurements of facial characteristics from eight pre-Columbian skulls found in The Bahamas. This technique is known as geometric morphometrics and offers a scientifically robust way of determining kinship. In other words, are these skulls from the same people? Or from different groups?

We also looked at craniofacial measurements of 95 pre-Columbian skulls from across the region: Venezuela, Cuba, Hispaniola, Jamaica, Colombia, Puerto Rico, the Yucatán, Florida and Panama.

We found that there were effectively three clusters of craniofacial similarity across the Caribbean, suggesting relatively close kinship ties. One cluster, from the so-called first wave of migration, was in Cuba and the Yucatán. The second cluster, from the Arawak expansion – or second wave – was in Venezuela, Colombia and Puerto Rico. But, and this is the exciting part, we also found that there’s a third cluster – from a Carib wave – in The Bahamas, Hispaniola and Jamaica.

Editor’s Note: You can read more about the work in this piece from the Florida Museum of Natural History.

This post was originally published in NC State News.