Forecasting October . . . in April

If you’ve ever been frustrated by rain on a day that was forecast to be sunny, you know that predicting the weather is no simple task. Imagine how hard it is to predict hurricane activity several months in advance.

Since 2005, an interdisciplinary group of NC State faculty and graduate students from the Departments of Statistics and Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences have been tackling this tricky task. They release an annual hurricane prediction forecast for each hurricane season, which runs from June through November.

Ever wonder how they do it?

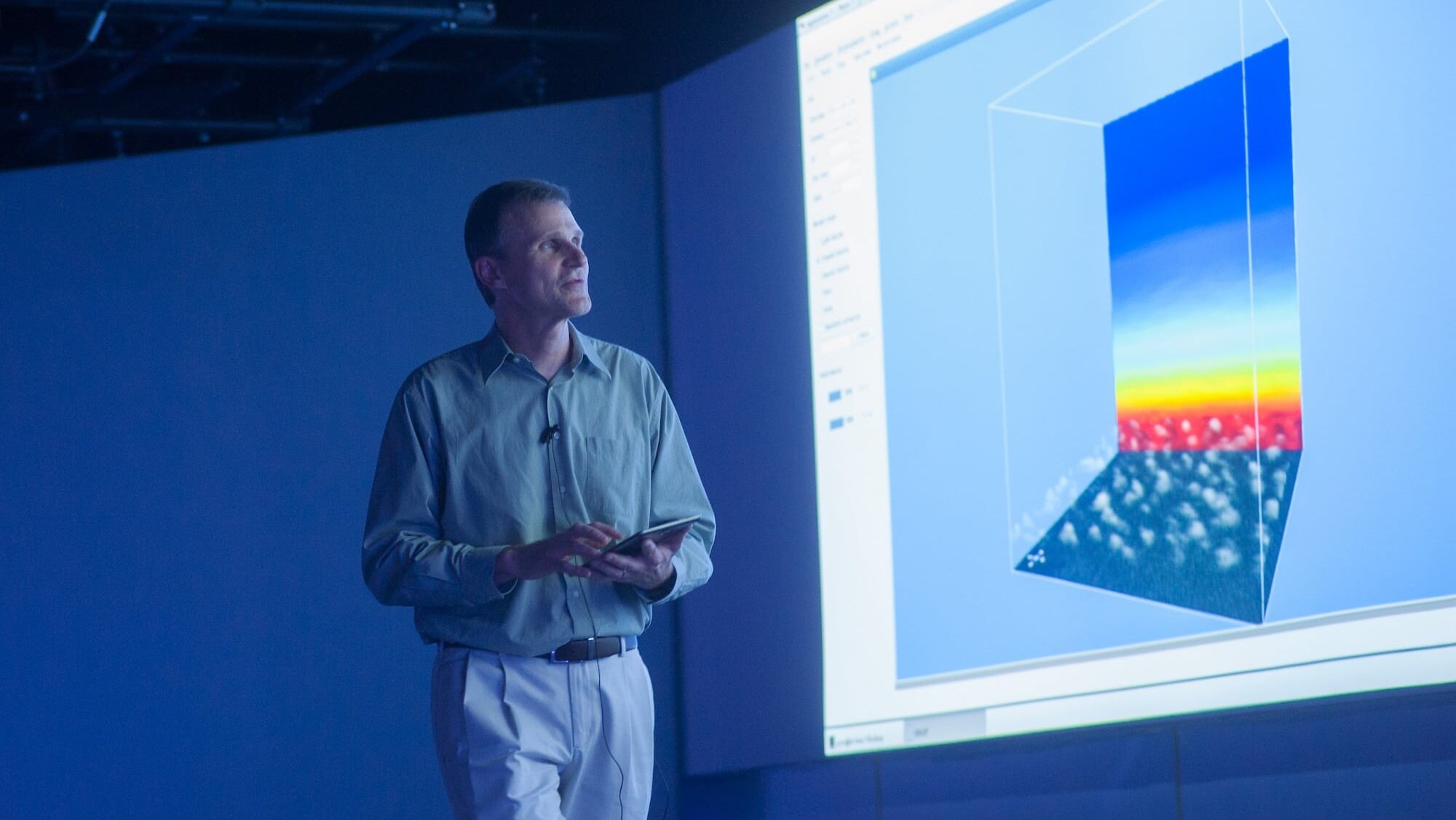

Lian Xie, a professor of marine, earth and atmospheric sciences, started developing the forecasts more than a decade ago. After years of following hurricane forecasts and noting their inconsistent accuracy, he decided to figure out how to improve them.

He soon realized that collaborating with statisticians would improve his work and invited statistics professor Montserrat Fuentes to join the project in 2006. Other collaborators have since come on board; this year’s team included Joseph Guinness, assistant professor of statistics; Marcela Alfaro-Cordoba, graduate research assistant in statistics; and Bin Liu, adjunct assistant professor in marine, earth and atmospheric sciences.

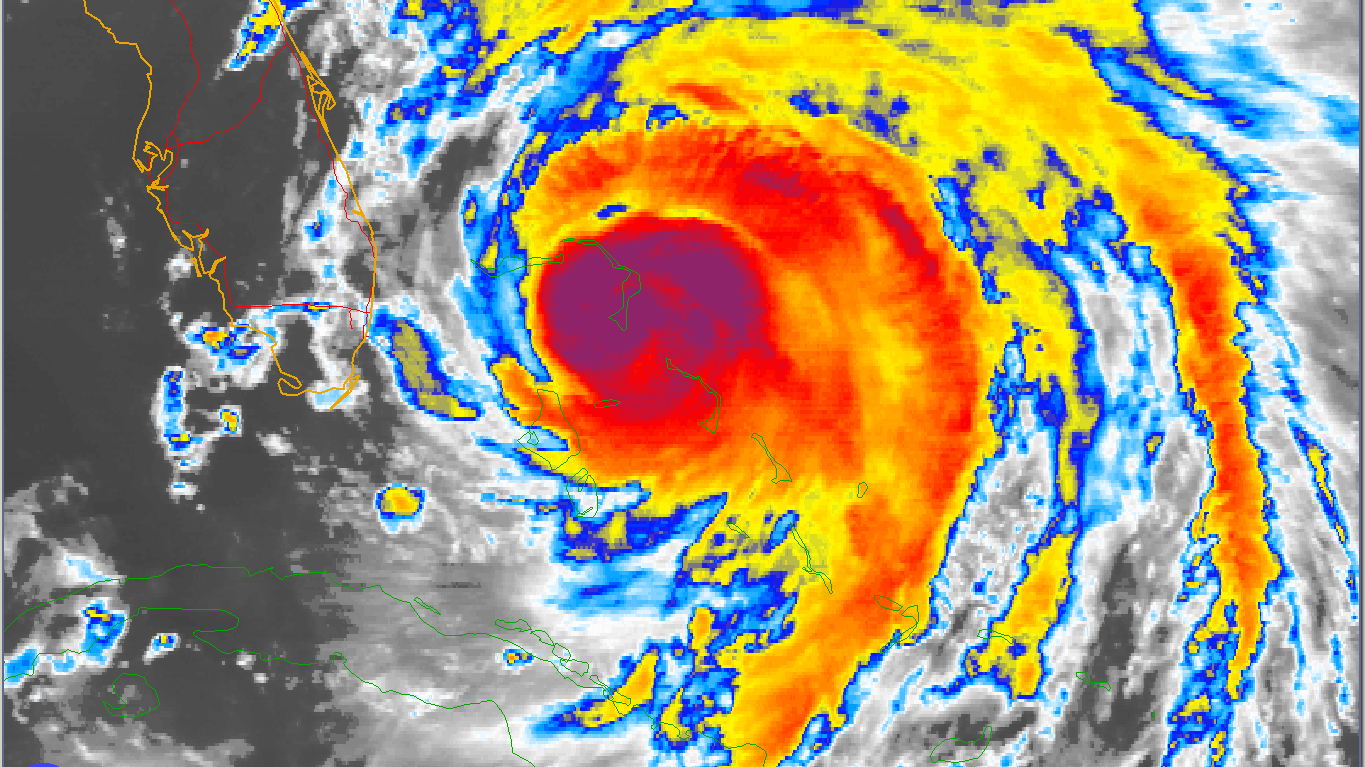

The team’s first step in developing their predictions is deciding what types of storms to forecast. For the last several years, they have released three predictions — hurricanes, major hurricanes and all named storms (tropical storms and hurricanes). They forecast these storms for each of three regions: the East Coast, the Gulf of Mexico and the Caribbean.

Next, they must determine what factors, or predictors, are likely to influence the forecast and how much weight to assign to each factor. More than 20 of these predictors can influence a typical forecast, including El Niño activity, water and air temperature in the Atlantic Ocean, and patterns of trade wind activity.

Each year, the researchers reexamine and shift the predictors and weighting system. Their recalibrations are often based on the success or failure of the previous year’s predictions.

Once they have weighted the predictors, the researchers run various statistical models using test data that helps them drill down to the most accurate model. Then they gather the data and forecasts related to the predictors — for example, water temperature data collected by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. But the actual data for some of the factors are not available before the hurricane season begins, so the team must rely on those data predicted in advance, adding a layer of risk to the forecast.

The team usually runs its final model by early April. The model shows probability distributions for each of the forecasts, which the researchers use to make their predictions.

But the process doesn’t end once the predictions are released. The researchers always evaluate the accuracy of each year’s forecast after the season ends to help them start thinking about the next year.

This year, the group predicts a more-active-than-average season in the Atlantic Ocean. Their forecasts have varied in accuracy over the years, but each one has helped them learn.

“In terms of scientific discovery, the incorrect forecasts are more valuable,” Xie said. “If you get it wrong, you have to figure out why, and you learn more.”