Toward Equality in Science

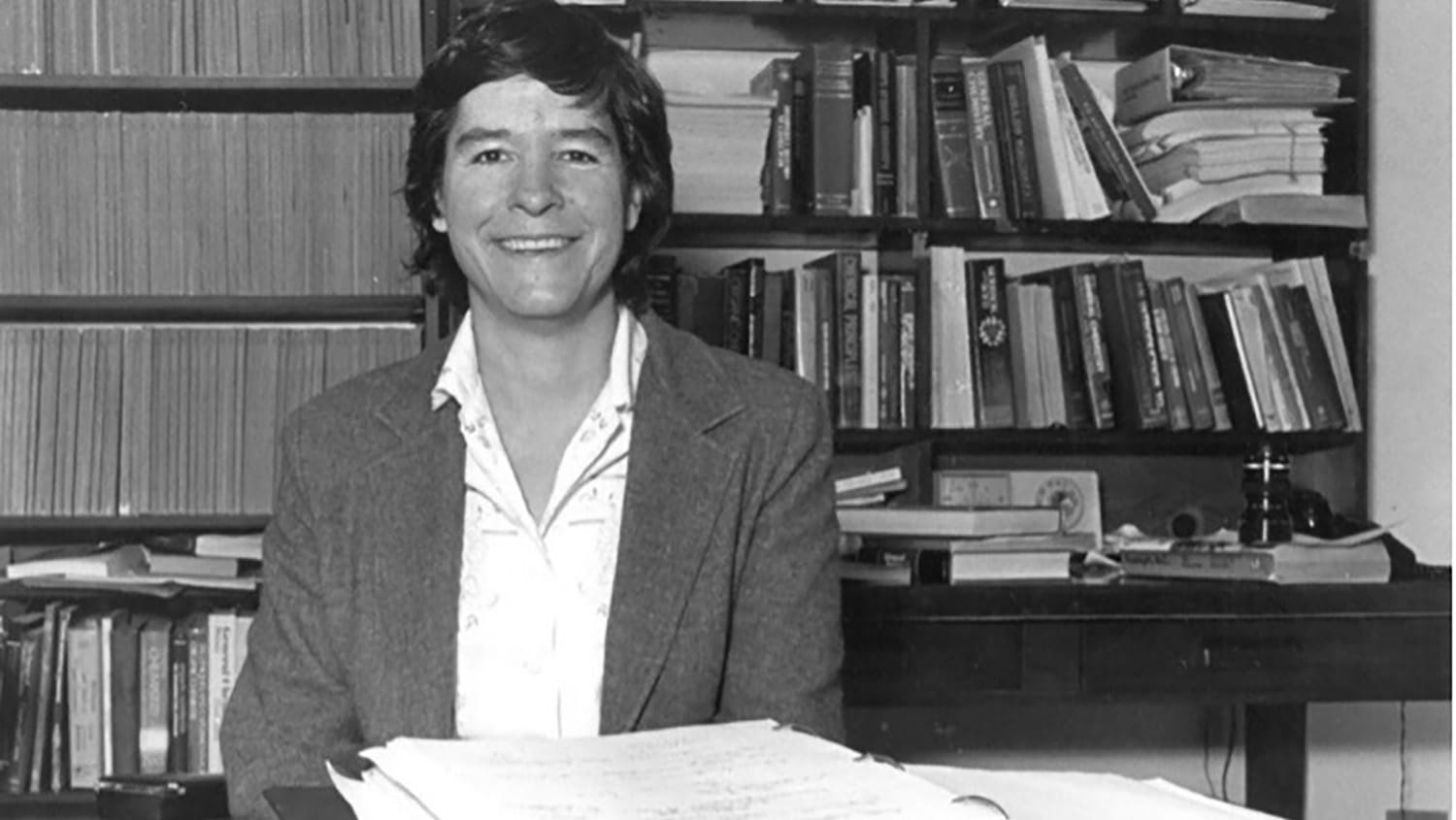

Madeleine Jacobs has worn many hats in her career: science student, reporter and editor. Most consequentially, she’s been a leader who has championed the cause of boosting the number of women scientists in academia and industry.

Jacobs, who until recently was the CEO of the giant American Chemical Society (ACS), came to NC State in April as the College’s second State of the Sciences speaker. State of the Sciences was the signature event of the Science Unscripted Events Series, which this year featured several events focused on diversity in the sciences.

When Jacobs began her science career, she never imagined she would need to be such a staunch advocate for change. As an undergraduate chemistry student at George Washington University, she was aware that there were few female faculty members in her department, but she felt comforted by the large number of women in her science classes.

“I just knew that things would get better, because I saw all these women in the science pipeline,” she said.

But that hasn’t necessarily been the case — and Jacobs has built a career finding out why. As a young reporter for Chemical & Engineering News (C&E News), a weekly news magazine of the chemical world published by ACS, she became intrigued by the disparity in the salaries between female and male chemists.

She went on to spend 21 years in science writing and public affairs before returning to the magazine as its managing editor and then, in 1995, as its editor-in-chief.

In 2004, Jacobs became the CEO of ACS, which with 161,000 members is the world’s largest scientific society. She stepped down earlier this year to become the president and CEO for the Council of Scientific Society Presidents.

Thanks to the efforts of Jacobs and others, there are more women studying science than ever before. In chemistry, for example, 36 percent of doctoral degrees are awarded to women today, up from just 8 percent in 1970.

But all those new Ph.D.’s haven’t translated into a representative number of leadership positions for women. Women made up only 13 percent of chemistry faculty who were full professors at top universities in 2012–13 (the last year for which C&E News conducted its survey). That’s up from 7 percent in 2002–03, but almost all those gains were realized in the preceding decade.

“What is terrible is that these statistics have not increased as rapidly as you might think,” Jacobs said. “In fact, in recent years they haven’t changed much at all. There was a large increase at first, but then it kind of dropped off.”

The data show a similar situation for women in leadership positions in industry. In a 2014 C&E News survey of 42 top chemical companies, only one had a female CEO. Eleven companies had no top women executives.

Jacobs offered a list of ways to open more doors for women, including urging everyone to be mentors for young women. She also encouraged women to find collaborators and develop personal agendas with five-year plans.

“Energy and perseverance do pay off,” she said. “I hope we can work together to make it happen.”

- Categories: