Shaping A Less Toxic Future

In a perfect world, every consumer product from furniture to water bottles would be tested for years before being deemed safe for use.

But that’s not how things work. Market forces speed products onto store shelves, and it’s hard to know how the chemicals in those products will affect the long-term health of those who buy them. Even less is known about how those chemicals will affect future generations.

Remember, lead was once considered a safe ingredient in paints.

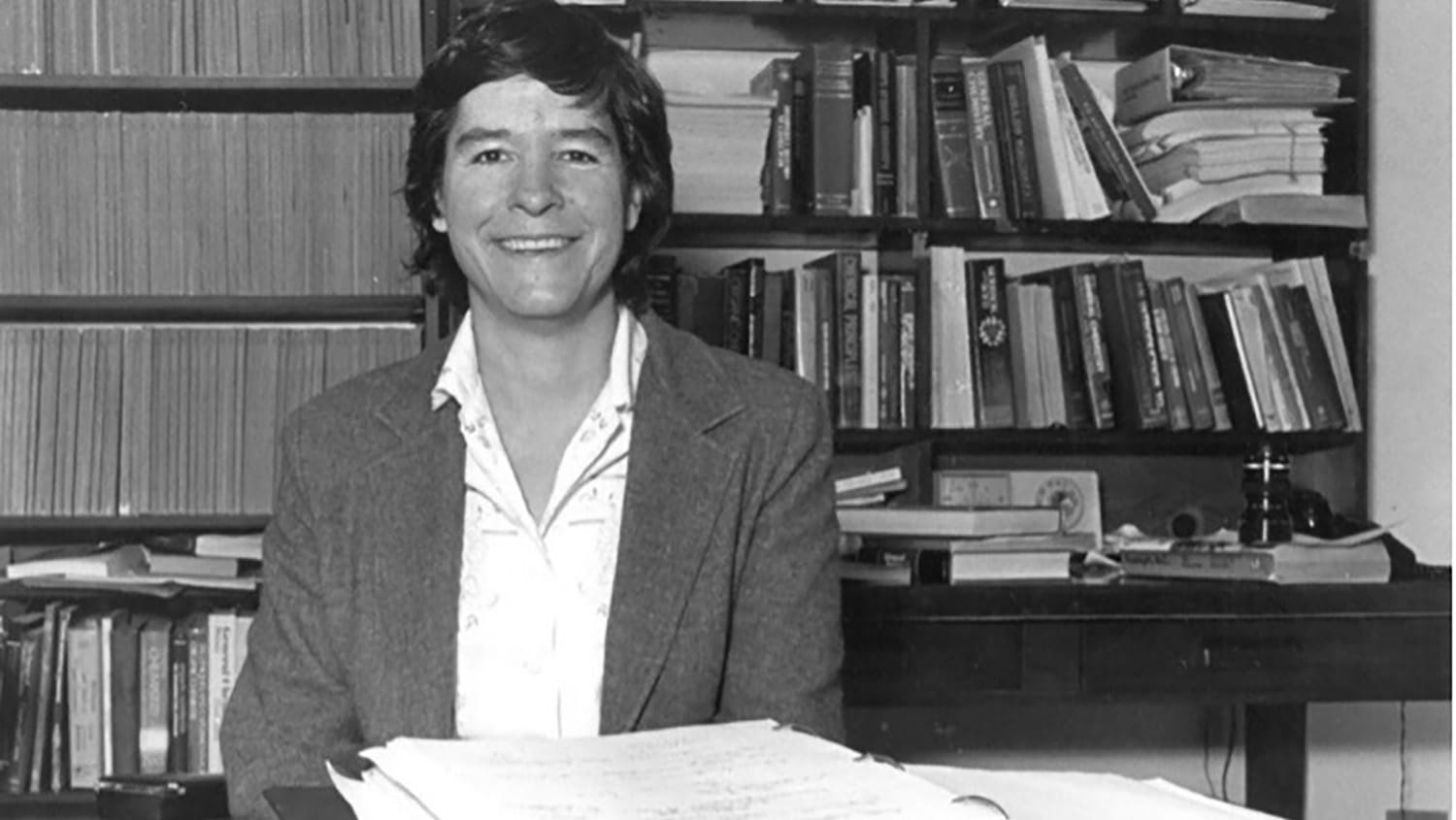

“These kinds of chemicals can stick around for a long time,” said Dr. Heather Patisaul, a professor of biological sciences at NC State. “It’s important to know how they can affect human health.”

Patisaul studies how chemicals are reshaping our brains, bodies and behavior. Her work is important because humans are swimming in a soup of over 85,000 chemicals, most of which have not undergone any toxicity testing. Each person is carrying around more than 400 such chemicals at any given time.

Her name is familiar to those who have followed the ongoing national conversation about Bisphenol A, a compound used in plastics that’s more commonly known as BPA. Manufacturers use BPA to make plastic containers sturdy and clear. But the human body treats BPA like an extra shot of estrogen, which can affect the body’s developmental, reproductive, neurological and immune systems.

Patisaul has been studying BPA for most of the past decade, using laboratory rats as her test subjects. Among other findings, her research has shown that early-life exposure to BPA can accelerate female puberty, alter the sex-specific development of the brain, and alter anxiety-related behaviors.

But Patisaul’s work extends beyond BPA. In collaboration with Dr. Heather Stapleton at Duke University, Patisaul is also studying Firemaster 550, one of the most popular fire retardants used in furniture. Firemaster 550 has replaced the discontinued, neurotoxic mixtures that were used in the 1980s and 1990s.

“Whenever a product is discontinued for safety concerns,” Patisaul said, “you have to ask, ‘What’s replacing it? And what are the dangers?’”

Patisaul’s research has shown that Firemaster 550 can accumulate in rat tissues and carry over to their offspring. The effects: weight gain, advanced puberty in females, and a condition that thickens heart chamber walls in males.

The problem with Firemaster 550 and many other replacement compounds, Patisaul said, is that U.S. regulatory structure doesn’t take into account that derivative compounds can be just as toxic as the originals.

For example, a popular replacement for BPA is Bisphenol S (BPS), which is structurally similar to BPA and, like BPA, appears to be an endocrine disruptor. As long as BPS does its job — make plastic sturdy and clear — at a comparable cost, many manufacturers are content to make the switch, she said.

“To stop this from happening, we would have to completely restructure how the industry thinks about product safety. But I think it’s something we can do,” Patisaul said. “Understanding the biology behind these products is so critical. If we understand how they affect obesity, brains and behavior, then maybe we can break the cycle of delivering harmful products to consumers.”

Thanks in part to the work of Patisaul and other researchers, manufacturers voluntarily removed BPA from baby bottles and sippy cups, and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) eventually banned the chemical’s use in those products. But BPA remains in use in other products.

Patisaul has made educating the public about her research part of her job. She’s testified before Congress, gives lots of media interviews, and frequently addresses groups at museums and schools.

Patisaul is also working with other researchers on an initiative called CLARITY-BPA. The FDA-sponsored research program combines more than 40 researchers from various fields to conduct further research into BPA’s safety.

“I think it’s really important to use an interdisciplinary approach for tackling problems like these,” Patisaul said. “I’m lucky to be at NC State. We have chemists, biologists, toxicologists, engineers — and you need all these people to work together to make effective change.”

Buy Smart

Heather Patisaul’s research on chemicals in consumer products has affected her own behavior and buying habits.

Plastic Avoidance

“I don’t use a lot of plastics. I pack my lunch in glass containers. My kids take their lunches and school supplies in glass. You’ll never find disposable plastic utensils in my house.”

Be Chemically Conscious

“I’ve developed a heightened awareness of the dangers of certain chemicals lurking around in everyday life. For example, it’s likely that most fragrances we use are endocrine disruptors, which can potentially cause all kinds of developmental disorders. The soaps, detergents, shampoo, sunscreens and cleansers in my house are all fragrance-free.”

Act Locally

“Changing federal and state laws is a tricky thing to do. I like to think local. Local issues are becoming more profound, and citizen participation is paramount. You have to vote with your green pocket.”

- Categories: