Nanoscopic Imaging Aids in Understanding Protein, Tissue Preservation in Ancient Bones

A pilot study from North Carolina State University shows that nanoscopic 3-D imaging of ancient bone not only provides further insight into the changes soft tissues undergo during fossilization, it also has potential as a fast, practical way to determine which specimens are likely candidates for ancient DNA and protein sequence preservation.

“Paleontologists have studied fossilized bones for centuries, but we still don’t completely understand the fossilization process for organic soft tissues of bone, like collagen protein or blood vessels, and how they preserve over extended periods of time,” says Landon Anderson, NC State graduate student and author of the research. “I used a nanoscopic imaging approach to compare modern bones and bones from the Ice Age, as a method for potentially better understanding the changes collagen protein and blood vessels undergo during fossilization.”

Anderson compared small samples of modern cow, alligator and ostrich leg bones to those from Pleistocene-era woolly mammoth, steppe bison, reindeer, and horse. The Pleistocene samples were all recovered from thawed, ancient permafrost in Canada’s Yukon Territory.

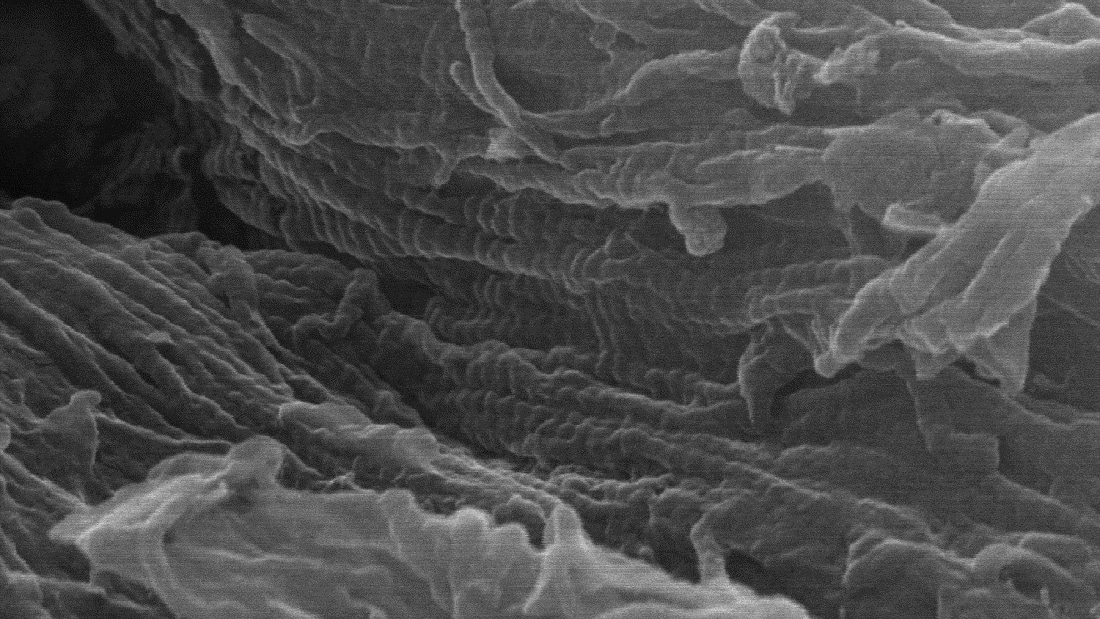

Applying a dilute acid solution to the samples dissolved the mineral portion of the bones, leaving behind their underlying collagen protein frameworks. Using scanning electron microscopy (SEM) up to 150,000x magnification, Anderson was able to image the collagen protein fibrils and blood vessels within the demineralized bone samples.

Anderson scanned the surfaces of the imaged structures using time-of-flight secondary ionization mass spectrometry (ToF-SIMS), which identified the chemical signatures present in the structures and helped further confirm them as collagen protein and blood vessels.

“The imaging data and ToF-SIMS showed that the Ice Age samples still consist of original, unfossilized bone tissue – they are subfossils and still preserve much of their original, unaltered organic tissue and proteins, similar to modern bones,” Anderson says. “The underlying idea of this pilot study is that this nanoscopic approach could be used on bones all across the fossil record to better understand the chemical and structural changes that occur to organic tissues during fossilization.”

The technique could potentially also be used as a proxy for screening ancient bone specimens for DNA and protein sequence preservation.

“The electron microscope imaging allows you to directly view the nanoscopic collagen fibrils of bone, which are essentially bundles of collagen protein molecules,” Anderson says. “Collagen protein is robust, so for an ancient bone specimen lacking these fibrils, if they’ve been degraded away, then there is also unlikely to be any recoverable DNA present in the sample and protein content would be reduced, at a minimum. This technique could be a practical first step to screen candidate specimens for further molecular analysis.”

The work appears in iScience.

-peake-

Note to editors: An abstract follows.

“Nanoscopic imaging of ancient protein and vasculature offers insight into soft tissue and biomolecule fossilization”

DOI: 10.1016/j.isci.2024.110538

Author: Landon Anderson, North Carolina State University

Published: July, 19, 2024 in iScience

Abstract:

Fossil bones have been studied by paleontologists for centuries. Despite this, empirical knowledge regarding the progression of biomolecular (soft) tissue diagenesis within ancient bone is limited; this is particularly the case for specimens spanning Pleistocene directly into pre-Ice Age strata. A nanoscopic approach is reported herein that facilitates direct imaging, and thus empirical observation, of soft tissue preservation state. Presented data include the first extensive nanoscopic (up to 150,000x magnification), 3-D images of ancient bone protein and vasculature; chemical signals consistent with collagen protein and membrane lipids, respectively, are also localized to these structures. These findings support the analyzed permafrost bones are not fully fossilized but rather represent subfossil bone tissue as they preserve an underlying collagen framework. Extension of these methods to specimens spanning the geologic record will help reveal changes biomolecular tissues undergo during fossilization and is a potential proxy approach for screening specimen suitability for molecular sequencing.

This post was originally published in NC State News.

- Categories: