Preparing East Africa for a Population Surge

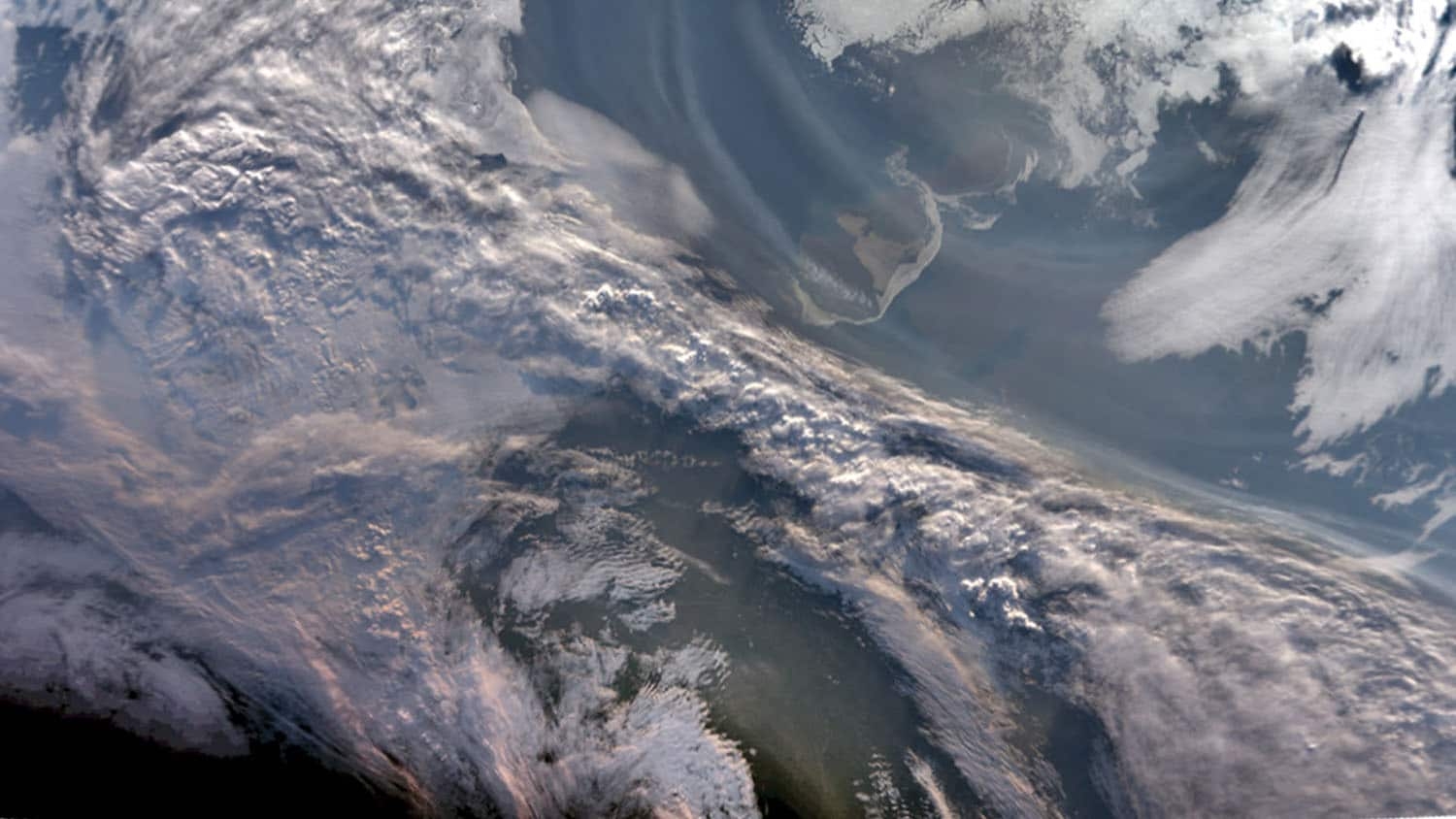

Sprawled across 26,000 square miles and straddling three countries, Lake Victoria has a footprint larger than West Virginia. It is the largest tropical lake in the world, and the second-largest lake overall as measured by surface area (Lake Superior is the largest).

The lake is also the social and economic nerve center for more than 30 million people who live in that fast-growing part of East Africa. They depend on the lake for food, water, transportation and hydropower.

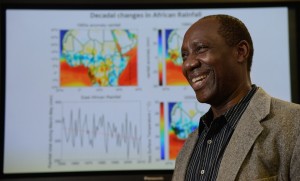

Enter Dr. Fredrick Semazzi, an NC State meteorologist and mathematician. For the past several years, Semazzi has been leading an international initiative to pair the latest weather and climate research with real economic-development planning, efforts that position him among the most important researchers in the world at the intersection of climate and policy.

The initiative, called the Hydroclimate Project for Lake Victoria (HyVic), brings together hundreds of climate researchers, internet providers, infrastructure developers and other groups of people who live around the lake. The idea is to provide the underpinning research for gauging the area’s changing climate and make that information accessible for policy makers and residents to make informed decisions as the region grows.

The project’s efforts include finding ways to reduce the number of deaths on the lake. Up to 5,000 people are killed fishing on Victoria each year, many as the result of severe weather and rapidly changing water currents.

“HyVic maximizes the effectiveness of science and minimizes duplication of resources so everybody knows who’s doing what,” Semazzi said. “This is the one-stop place to systematically prioritize how this region plans for future climatic conditions.”

The work is particularly important because the population of the Lake Victoria basin — an area that includes the lake-bordering countries of Kenya, Tanzania and Uganda — is expected to rise 500 percent by 2030. That makes the basin one of the fastest-growing areas in the world and puts extreme pressure on its natural resources.

HyVic, which has been in the planning stage for four years, passed an important milestone in December when the World Climate Research Program (WCRP) gave the project its full approval. The program is backed by the United Nations and some of the world’s leading climate-related institutions: the World Meteorological Organization, the International Council for Science and the Intergovernmental Oceanographic Commission of UNESCO.

With the approval came the creation of an international science panel chaired by Semazzi; an international project office will be established soon. These activities cement HyVic as the umbrella organization under which researchers can access funding from international organizations.

The work has special meaning for Semazzi, who was born in Uganda and received his undergraduate and graduate degrees in Kenya. He has been a full professor at NC State since 2000, using high-powered computers to develop advanced climate models, some of which have improved predictions of hurricane activity. His work in Africa, considered some of the most important of its kind, has included the development of a new weather-based tool to improve distribution of meningitis vaccine.

About five years ago, he shifted his focus from model development toward work that more directly affected people’s lives. It was around this time that he became involved with HyVic, and NC State supported his efforts to lead a feasibility study on the project.

“NC State has a lot to be proud of,” he said, “because the credit goes to this university for what has happened with HyVic.”

Semazzi’s HyVic-related research is focused on what’s known as the “Lake Victoria Basin Climate Change Paradox.” For years, climate models have been projecting that a warming planet will increase rainfall in the basin and cause the lake to rise. But lake levels have actually been declining due to a decades-long drought — hence the paradox.

Traditional thinking has blamed the drought on weather patterns in the Indian and Pacific oceans. But Semazzi has found new evidence concerning the critical role played by weather in the Atlantic Ocean. The Atlantic’s contribution, Semazzi said, helps explain a major part of the paradox and seems to indicate that the drought will linger.

This type of information is important for policy makers in the basin. Among the planned economic-development projects are the construction of expensive hydroelectric dams on the Nile River, which drains the lake. Stable energy sources such as hydropower are important to such a fast-growing region, because without reliable energy the area could become unstable and violence could erupt.

“But if the drought will be prolonged for another few decades,” Semazzi said, “that calls into question whether those dams will need to be operational anytime soon.”

Beyond HyVic, Semazzi is part of a team of researchers who have started a similar planning organization that focuses on all of Africa. That project is still in its early stages, but HyVic, and Semazzi’s leadership, serve as models.

“I see HyVic as a way to consolidate my areas of expertise,” he said. “It gives me an opportunity to combine all those experiences in a single project that helps people.”