On Sept. 16 — the 2020 Day of Giving — Graduate School Dean Peter Harries sent a note to alumna Jessie Rivers, thanking her for her gift to the Graduate Education Enhancement Fund. Rivers wrote back, explaining how much she valued her graduate experience at NC State and how it continues to shape her career.

Growing up in the Northeast corner of North Carolina, Jessie Rivers didn’t think a lot about attending college. But when a close friend chose to attend Meredith College in Raleigh, Rivers decided to follow in her friend’s footsteps.

That decision put Rivers on the path to earning a Ph.D. in organic chemistry from NC State University and later to two industry careers in chemistry. Today, Rivers is a chemist with JLA Global in Edenton.

At Meredith, Rivers started out as an art major, but the lack of structure in the program caused her to reconsider. “I didn’t have a grand plan; I just wanted to go to college. But the art teacher showed up once a week and said, ‘What have you created?,’” Rivers said.

“I couldn’t cope with that, because I’m one of the students that goes to every class, I sit in the front, I take copious notes. I learn everything, memorize it, and then I get to make a good grade on the test. So I didn’t do well with just having to be creative,” she said.

Rivers changed her major to home economics, which included a required course in organic chemistry with Mary Yarbrough, who was head of the Meredith chemistry department at the time. At NC State, Yarbrough is recognized as the first woman to earn a graduate degree in 1927. She served on Meredith’s chemistry faculty from 1929-1972.

“(In home economics) we were supposed to be able to understand food chemistry terms like polyunsaturated and partially hydrogenated. I did well in the class, and Dr. Mary is the one who talked me in the changing my major to chemistry going into my junior year,” Rivers said.

“And the other thing is, my parents couldn’t afford to send me to college anyway,” Rivers said, adding jokingly, “And it just came to me that here I was in college, and they were paying good money to for me to learn how to cook a chicken.”

Rivers described Yarbrough as “friendly, warm and welcoming. I never saw her treat any student differently. She was very much about encouraging us to work hard, to be successful.”

Yarbrough serious about lab safety, making sure that students wore safety glasses and followed proper lab procedures, Rivers said. Yarbrough also invited small groups of students to her home near Meredith’s campus. “She was dedicated to education. And of course, her love and interest was chemistry,” Rivers said.

Rivers married an NC State alumnus two weeks after graduating from Meredith, and the newlyweds moved to Sanford. But within three months, Rivers knew she needed a new challenge. She was accepted into the Ph.D. program for chemistry at UNC-Chapel Hill in the fall of 1971. But she didn’t find the program to be a good fit, so in the spring semester of 1972, she transferred to the Ph.D. chemistry program at NC State.

She doesn’t recall if there were other women in the program or on campus. She commuted to campus daily from Sanford, so for her, the program was more like a job.

She remembers her mentor and advisor, Samuel Levine. Her research involved the synthesis of cinchona alkaloids, naturally occurring compounds like caffeine and nicotine. Through synthesis, chemists learn and understand how chemicals react with each other, Rivers said.

“You put chemicals in the same pot together and try to get them to do what you want them to do, to react. There are a lot of synthetic chemicals that are nature-identical, like menthol, for example, that is put into cigarettes,” she said.

Rivers was sure that her organic chemistry degree would help her find a job at a pharmaceutical company, but when she graduated in 1977, there were no jobs to be found in that industry. She applied for jobs with two large tobacco companies – R.J. Reynolds Tobacco and Philip Morris – and RJR offered her a job. So she and her husband moved to Winston-Salem, where she worked for RJR Tobacco’s organic synthesis group.

“RJR had done a lot of work prior to that time trying to isolate chemicals from tobacco and tobacco smoke. So the organic synthesis group’s task was to try to synthesize these chemicals that they thought were present in the tobacco or tobacco smoke. And then once you synthesized it, you took properties and studies and compared them so you could confirm or disprove the presence of that chemical,” Rivers said.

“So it was like a dream to go right out of grad school into doing something you were trained on and knew how to do,” she said.

By 1991, Rivers was divorced with two children, and she felt like she needed to live closer to her family in Coinjock, NC. RJR had a research farm in Bertie County, so she moved to Edenton to work at the farm.

After two years, Rivers decided that she wanted to try a career in education, so she took some courses at ECU. She later decided that education wasn’t the path she wanted to take. “I never even got the teaching certificate,” she said. “I tried the classroom and could not do it.”

So she decided to return to the lab as a chemist with JLA Global in Edenton. “I came back to the lab where the instruments don’t talk back, and they don’t leave when you are talking to them,” she said.

JLA Global is engaged in food quality and safety testing. The lab analyzes food products for nutrition labeling. “If you look on a food label, you see things like how much fat, how much moisture, how much protein is in the product, and so forth. We do all those kinds of tests,” Rivers said.

One of the most important functions of the lab is testing peanuts for aflatoxins, naturally occurring toxins produced by a mold called Aspergillus flavus. The service is important for helping U.S. peanut growers sell their product safely at home and abroad.

After 17 years with RJR Tobacco and now 25 years with JLA Global, Rivers has enjoyed her industry career. The work has brought her full circle, back to food chemistry which first piqued her interest at Meredith College. “Over the years I received excellent on-the-job training in chemistry, chromatography, statistics, leadership and communication, and I made lifelong friends,” she said.

She offers this advice to graduate students interested in an industry career.

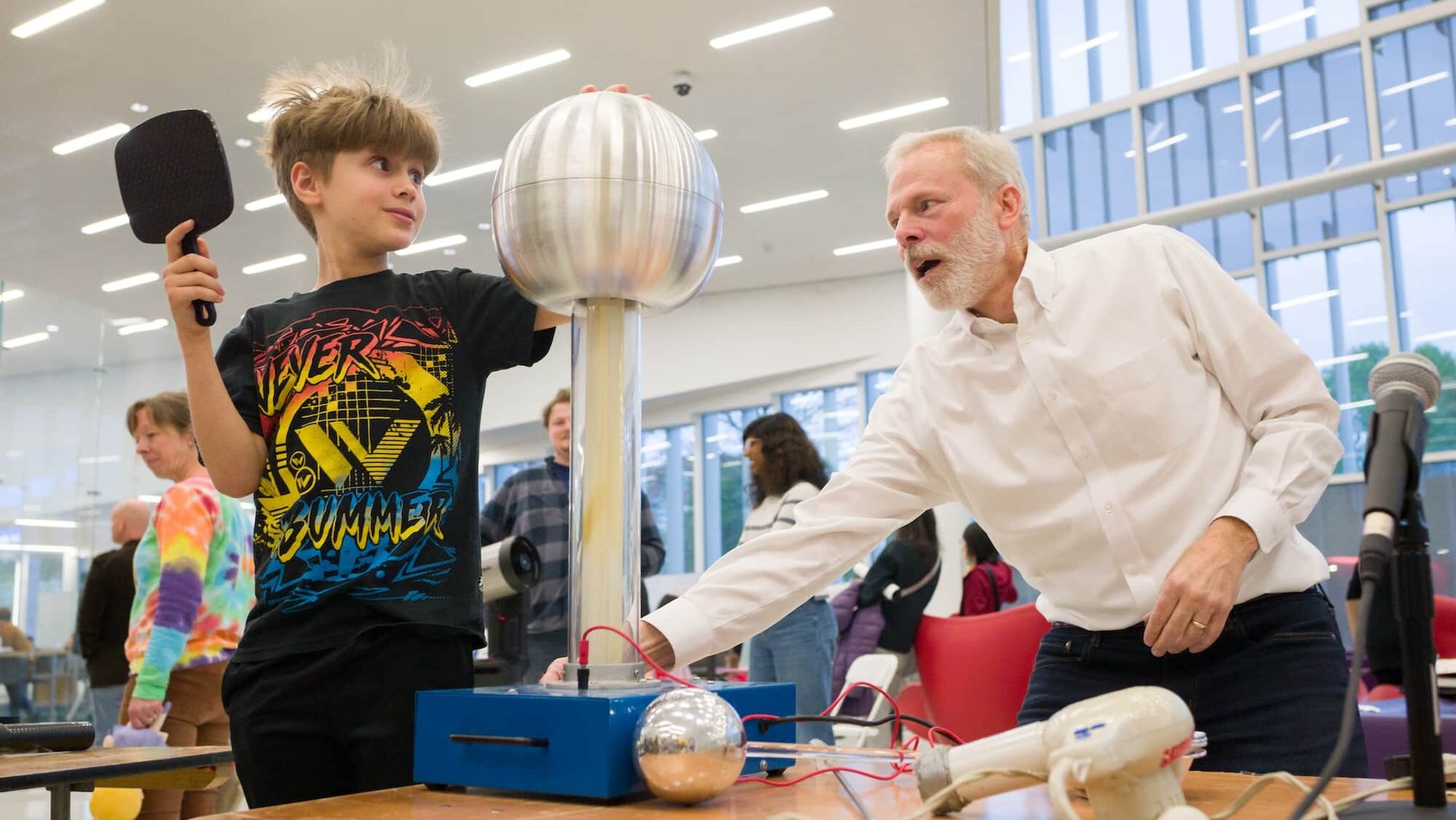

- Be flexible as you change career phases. Rivers illustrates this for students by hitting a rubber hose with a hammer before and after putting it into liquid nitrogen. When frozen and inflexible, the hose shatters, and you can’t put it back together.

- Use the internet to research any career interest you have. You can virtually “interview” any company all by yourself. Explore their websites, and research their people through LinkedIn. Teach yourself about regulatory and safety requirements for the work.

- Join a professional organization, such as the American Chemical Society, and subscribe to their publications.

- Learn to use computer tools like the Microsoft Snipping Tool. These skills are invaluable in your professional and personal life.

This post was originally published in The Graduate School News.

- Categories: