Winners of the 2017 NC State Research Image Contest

From a map of Mars to a mid-strike lightning bolt, the College of Sciences winners in this year’s NC State Research Image Contest captured the scope and beauty to be found in seeking to understand the world around us.

The contest was open to faculty, staff, graduate students and postdoctoral researchers. The program is funded by NC State’s Graduate School and Office of Research, Innovation, and Economic Development, with support from the college and University Communications.

The college’s winners are below. You can get an in-depth description of the winning entries in each category by clicking on the category headline, or see the full list of related posts here. A slideshow of all the winning entries (except the videos) can be found on Flickr.

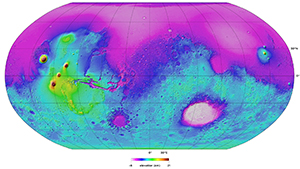

First place for graphics and illustration among faculty and staff goes to a Mars map from Paul Byrne, an assistant professor in the Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences who specializes in planetary geology.

“The planet Mars has fascinated humanity for thousands of years,” Byrne says. “Recent spacecraft missions have returned an unprecedented view of the Red Planet, equipping us with new information with which to understand Mars’ geological history. Here, topographic data for the entire planet show the vast, low-lying plains to the north, enormous impact basins in the southern hemisphere and, to the west, the largest volcanoes in the solar system – the tallest of which, Olympus Mons, towers 21 km above its surroundings!

“Mars is very like our own world in some respects, yet vastly different in others,” Byrne adds. “Exploring the Red Planet in three dimensions – that is, with both photographic images and topography – we can start to investigate questions impossible to tackle with images alone. As a result, data sets like this one (global topography from the Mars Orbiter Laser Altimeter instrument, flown on NASA’s Mars Global Surveyor) enable us to understand when and where volcanic activity was prevalent on Mars, for example, which in turn tells us when the planet was geologically active, and possibly why it’s no longer active today.”

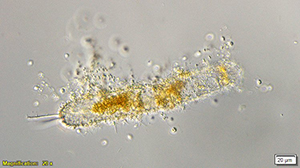

Second place for microscopy among graduate students was awarded to Gabrielle Corradino, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, for the image she titled “Nano-Hitchhikers.”

“Nanoflagellates are single-celled planktonic eukaryotes ranging in size from two to 20 microns and can have various nutrient strategies,” Corradino says. “These organisms (not sharks), may be considered the mightiest predators in the ocean. In this image we see over 30 nanoflagellates ‘hitching’ a ride from a larger phytoplankton cell. In some cases, nanoflagellates can infect plankton in marine waters, which plays a significant role in energy transfer and nutrient cycling through marine food-webs.

“Nanoflagellates remain one of the least-characterized members of the marine microbial food-web,” Corradino says. “Understanding their species-specific physiology and trophic interactions is necessary as we aim to forecast energy flow and potential plankton regime shifts in response to anthropogenic stressors in our oceans.”

The winner in the graduate student category for photography is Andy Wade, a Ph.D. student in the Department of Marine, Earth and Atmospheric Sciences, who captured lightning in mid-strike in a photo he titled “July 12, 2015” (the photo at the top of this post).

“The photo was taken when graduate students from NC State, the University of Oklahoma and Colorado State University were collecting data on a line of passing storms in southeastern Minnesota,” Wade says. “The Plains Elevated Convection at Night (PECAN) experiment sent researchers from numerous universities and laboratories across the central U.S. in search of nocturnal thunderstorms.

“Nighttime thunderstorm complexes are responsible for much of the Great Plains’ warm-season precipitation, sometimes produce severe weather and influence weather far downstream,” Wade explains. “Improved understanding of their formation and dynamics will benefit agriculture and yield better forecasts.”